… Hails supports of Governor AbdulRahman AbdulRazaq for the Armed Forces

The Chief of Defence Staff, General Olufemi Olatubosun Oluyede, has launched Operation Savannah Shield in Kwara State as part of renewed efforts to tackle insecurity and criminal activities across Kwara and neighbouring Niger State.

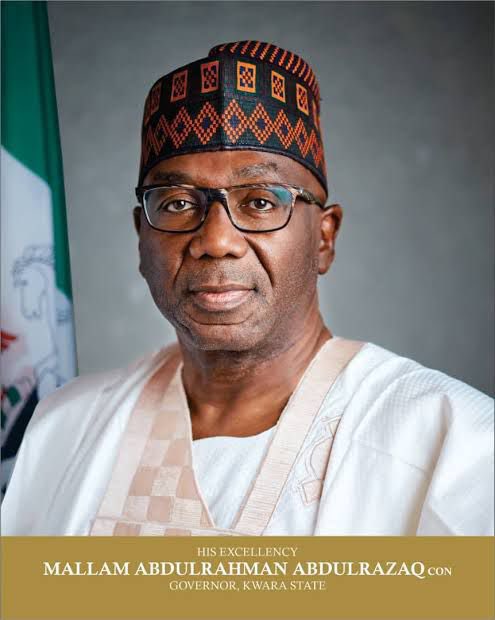

Speaking during a courtesy visit to Governor AbdulRahman AbdulRazaq, the Defence Chief said the operation was designed to checkmate criminal elements responsible for recent security challenges within the region.

Oluyede said his visit also served as an opportunity to commiserate with the government and people of Kwara State over casualties recorded from recent security incidents.

“Your Excellency, I am here briefly to pay homage. The essence of my coming to Kwara today is to launch Operation Savannah Shield,” he said.

He explained that the new operation is a joint task force bringing together combat units from different security formations to strengthen coordinated responses against insecurity.

According to him, the Armed Forces have aggregated personnel and operational assets under a unified command structure to improve effectiveness on the field.

“With this robust approach, we believe that things will get better within Kwara and Niger States,” the Defence Chief stated.

Oluyede acknowledged the security pressures facing the Armed Forces and appealed for continued collaboration between federal and state authorities, noting that logistics and operational support remain critical to achieving lasting results.

He specifically commended Governor AbdulRazaq, who also chairs the Nigeria Governors’ Forum, for his consistent support to the military and security agencies nationwide.

“It is important for me to put it on record that you have been very supportive, not only to the Brigade but to the entire Armed Forces of Nigeria,” he said, adding that sustained cooperation from state governments would further strengthen ongoing operations.

The launch of Operation Savannah Shield is expected to enhance intelligence sharing, improve rapid response capabilities, and restore confidence in communities affected by security threats across the Kwara–Niger corridor.